Are y’all curious about the mighty brisket? Well, my fellow brisket-devouring carnivores, you’ve come to the right place! In this post, we’re going to learn all about this classic cut of meat that’s been the centerpiece of American barbecue for generations.

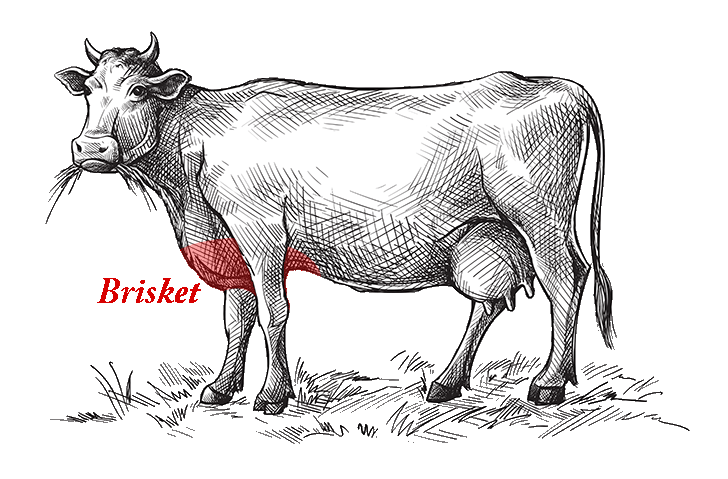

Alright, let’s waste no more time and get to the meat of it. I take it you found yourself wondering: “Where in tarnation does brisket come from on a cow?” Let me tell you, it ain’t from the finest part of the cow, that’s for sure. (Then again, it doesn’t really need to be. But we’ll get to that in a moment.)

The brisket comes from the cow’s lower chest, smack-dab between the front legs. It consists of the cow’s pectoral muscles, or as some might say, the “pecs”.

If you’re a seasoned pitmaster, then you know that what I just said about the brisket’s location tells us a whole lot about why it is the way it is, and why we cook it like we do. But for those of you not in the know, I’m about to break it down for you.

Why the Brisket Is So Lean

The chest muscles of the cow carry a whole lot of weight. As a matter of fact, they support about 60% of the animal’s body weight! And as a cow goes about its business, standing and moving around, those muscles get put through the wringer and get worked all the time. All the time, y’all!

It’s no wonder, then, that brisket is one tough and muscular cut of meat, with plenty of connective tissue to match. That connective tissue, called collagen, is what gives firmness and structure to the pectoral muscles — the firmness and structure required to carry all that weight minute by minute, hour by hour, and day by day.

Just compare the texture of a raw brisket to a raw steak, which comes from the fatty back area of the cow, and it won’t take you long to see what I’m rambling on about. The brisket is lean, tough, and muscly. The steak, fatty, beautifully marbled, and awfully tender to the touch.

Why We Smoke And Not Grill Brisket

Cooking does many things to meat, but it comes down to applying heat to make it edible. Now, depending on the cut of meat, “edible” can mean different things.

A steak is edible as soon as it’s tender enough to eat and cooked to safety. That is, the internal temperature has been brought to 145°F, give or take 10 or 15 degrees depending on the desired level of doneness, which gives the meat an appealing texture and kills the majority of disease-causing bacteria on its surface.

We grill steak because steak is relatively thin and very fatty. It doesn’t take the heat long to get to the center of the meat and cook it through. And as it does, the intramuscular fat in it, called marbling, melts away to make the meat deliciously tender.

Brisket’s a little different.

A brisket is lean and rich in collagen. Compared to a steak, it’s also much, much bigger.

The size of the brisket means it takes the heat a long time to penetrate all the way to the meat’s center. The fact that the brisket contains collagen means that it ought to be cooked to a much higher temperature than that of steak. Whereas marbling melts at temperatures close to 150°F, collagen doesn’t turn to gelatin until it’s reached temperatures close to 200°F.

This warrants low, slow cooking — be it in a braise or stew on the stove, in the form of a slow-roast in the oven, or in the company of smoldering hardwood in the confines of your smoker. Only by cooking the brisket low and slow can you cook the meat through all the way to the center and heat it to an internal temperature high enough to melt away the collagen without burning the bark and leaving it tasting the exterior of the meat like coal.

Bottom Line

The brisket, a formidable cut of meat, comes from the cow’s chest area. It constitutes the cow’s pectoral muscles (a.k.a. the pecs), which get worked a lot while the animal is alive and kicking. Because of that, the brisket low in fat and rich in connective tissue. It is also why it ought to be cooked low and slow, until that tough connective tissue melts away and turns into that mouth-watering juice called gelatin.