Grilling is a science as much as it is a craft, and having a scientific mind about how you grill will lead to better results.

That is, you’ll understand the results of your grilling better, as well as how to grill quicker, more effectively, and safely. But above all, with a bit of knowledge about chemistry and biology, you can grill some superb meat.

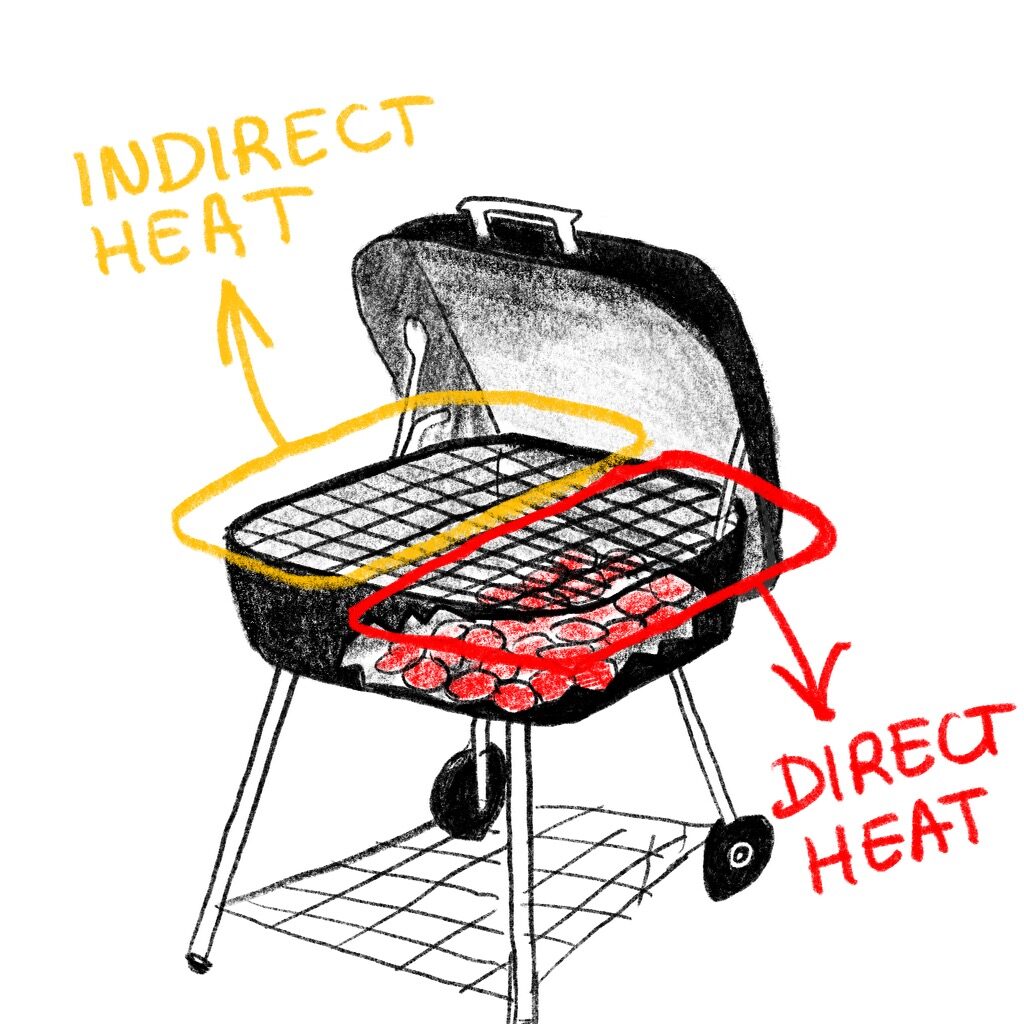

The main thing to know about grilling is that it’s a dry-heat cooking method, whether it be direct or indirect. Using both direct and indirect heat will get you a crispy outside and a juicy inside. You simply need to know how to make the most of them.

Let’s break down direct and indirect grilling methods so you can use them to the fullest advantage next time you’re at the grill.

What’s the Difference Between Direct and Indirect Grilling?

The words ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ are already a bit of a giveaway. In plain English, direct grilling is where the meat is directly above the source of heat, while indirect is near the heat.

Mark Bittman in his book How to Cook Everything explains the difference between direct and indirect grilling best:

There’s direct-heat grilling, where you put the food on a grate set right over a hot gas flame or charcoal to crisp, darken, and cook quickly. And there’s indirect-heat grilling, with the food off to the side of the fire and the lid on, so the grill works like an oven and cooks foods more slowly.

Mark Bittman, How to Cook Everything: 2,000 Simple Recipes for Great Food

So when using direct heat, you grill food quickly, precisely over the coals or burners, and with the lid off. When using indirect heat, you grill food slowly, slightly away from the coals or burners, and with the lid on.

You can think of direct-heat grilling as more like searing meat on the stovetop, and of indirect-heat grilling as slow-roasting meat in the oven. (The farther it is from the heat source, the slower it cooks.)

Here’s an illustration we made to help you see the difference:

What Is Direct Heat?

The rundown: Grill the food directly over the source of heat with an open lid.

Direct heat is probably what you are most used to when grilling meat. We all know at a basic level when grilling that the meat should be above the source of heat—and the closer it is, the faster it’ll grill.

Direct heat can also be referred to as ‘conduction’ when in direct contact with the meat, or if the flame is on the other side of a pan. But the problem with grilling only on direct heat is that while the food may look cooked on the outside, the heat fails to penetrate the interior, leaving it undercooked.

Undercooked vegetables are a texture issue, but undercooked meat is a matter of food safety.

This is where indirect heat comes into play.

What Is Indirect Heat?

The rundown: Grill the food near—but not over—the source of heat with the lid closed.

Indirect heat, whether it be on the grill or anywhere else, is heat that radiates out from the source. Indirect heat is not as hot as direct heat and is found further away from the source.

It’s like when you sit at a warm fireplace on a cold day. You don’t put your hands super close to the flames, just close enough to warm you up nicely.

Indirect cooking is similar to cooking in the oven. Harold McGee says in On Food and Cooking: “In contrast to the grill, the oven is an indirect and more uniform means of cooking.”

What Do You Grill With Indirect Heat?

The rundown: Thin cuts and sliced vegetables warrant direct heat. Thick cuts, whole birds, and intact vegetables warrant indirect heat. But briefly exposing them to direct heat ameliorates their flavor and crisps the crust.

Some foods should only be cooked over direct heat. Others benefit from some direct heat but require mostly indirect heat to cook through. For best results, you often have to use both.

Thin foods, such as thin steaks or bacon, for example, will not need to be grilled with indirect heat because heat can easily travel through them when placed directly on the grill and cooked thoroughly.

In fact, if you try to cook thin foods over indirect heat, they will dry out by the time they’re done.

Anything thick, hard, or whole that takes a long time for heat to penetrate and properly cook should be slowly grilled indirectly.

Should I Grill Vegetables With Direct or Indirect Heat?

Vegetables benefit from both direct and indirect heat. “When you expose the surface of vegetables to intense heat, the outsides will cook much faster than the insides,” Bittman says, just like meat.

The thickness also matters. Whole sweet potatoes, for example, need slow cooking with indirect heat to cook to tender in the middle. Again, as you would with thick cuts of meat or whole birds.

And with particularly thick vegetables, Bittman recommends “either slice them fairly thinly or grill them part of the time over indirect heat with the lid of the grill closed.”

The reasoning is simple: the direct heat of glowing charcoal or lit burners is often too high and too close to cook large pieces of food without burning them up on the outside.

Gentler cooking is required.

Should Chicken Be Grilled on Direct or Indirect Heat?

Chicken is a good example of meat that greatly benefits from indirect grilling and then direct grilling. There are a couple of reasons for this.

The first reason is safety and not to risk wasting your chicken. Particularly with chicken parts, solid fats can fall into the heat source and flare-ups can kiss the skin of the chicken, blackening it. Grilling chicken indirectly avoids that.

When grilling chicken pieces, Bittman recommends cooking over indirect heat for 20 minutes. Once cooked through, take them off the grill, add sauce, then return them to the grill directly above the heat.

How Do You Grill on Indirect Heat?

The rundown: Have an area without charcoal, or, on a gas grill, an area with unlit burners. This, along with closing the lid, is how you create indirect heat.

To grill on indirect heat, or what is known as a ‘low-heat area,’ as Harold McGee calls it in his Keys to Good Cooking, you first need to dedicate a grilling area, or multiple grilling areas, specifically for it.

On the topic of grilling vegetables, Bittman also says “as a general rule, keep a portion of the grill free of coals or gas to move things over to indirect heat if needed” but applies to any time you’re grilling.

So, don’t fill the whole bottom of the grill with charcoal as that’ll mean you will only get direct heat. Leave some space below the grill grate. On a gas grill, don’t turn all burners to the same setting. Light half, leave the other half off.

Another golden rule is to wait for the charcoal to ashen over and to always preheat the gas grill for 15 minutes before you get cooking.

With charcoal, this allows the coals to burn slowly and evenly.

With gas, it gives the heat enough time to start radiating off metal surfaces inside the unit—cooking the meat from multiple directions and resulting in a more even cook.

If you’ve ever slammed a frozen pizza in an oven immediately after turning it on, you’ve probably noticed that the results are uneven. Some areas may end up crunchy or burned, while others are cold, wet, or uncooked.

It’s all because you didn’t heat the oven first. The grill is no different.

Direct-Heat Grilling Method

Direct grilling is the best method for getting those meaty flavors to come alive.

Reaching around 284°F (140°C) is optimal for browning meat and developing the meaty flavors we all love.

This is called the ‘Maillard reaction,’ and when this happens, particles in the meat begin to smash into each other and explode with rich flavors and aromas. You need dry heat to do this—it cannot be achieved by boiling, as the water boils at 212°F (100°C) and its temperature doesn’t rise beyond this.

An article by Lone Mountain Wagyu explains that the Maillard reaction is caused by sugars and amino acids, saying:

“When these sugars and amino acids meet over high heat, they manifest as that luscious brown color and deeply complex flavor.”

As impressive as the Maillard reaction is, don’t forget that you’ll still need to make sure the inside is cooked too!